Feller Daniel (Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands)

Chiarotto Alessandro (Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands)

Koes Bart (Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands)

Maselli Filippo (Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy)

Mourad Firas (Department of Health, LUNEX 50, Avenue du Parc des Sports, 4671 Differdange, Luxembourg)

Although benign in most patients, it is estimated that 1% of neck pain can be the early manifestation of severe pathologies, such as malignancy and cervical arterial pathology. As standard practice, red flags (i.e., items from a patient’s medical history and clinical examination potentially associated with a higher risk of serious conditions) have been used to guide clinicians in identifying serious cervical pathology. 1,2 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no systematic review has been published investigating the recommended red flags for neck pain in clinical practice guidelines. Furthermore, knowledge of which study design the red flags recommendations were based on may help clinicians to value the recommendations’ strength. Therefore, we aimed to: 1) identify red flags to triage serious pathologies recommended in international clinical practice guidelines for neck pain, 2) evaluate the consistency in red flags recommendations across guidelines, and 3) investigate the strength of evidence, including on which study design the recommendations are based on.

The study protocol was registered a priori on MedRxiv. 3 Without time and languegae restriction, we searched for guidelines focusing on specific and non-specific neck pain in MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE, and PEDro electronic databases on 09/06/2023. Guidelines were also searched through forward and backward citation tracking strategies (Web of Science on 12/07/2023), by consulting experts in the field (top 10 experts on neck pain according to ExpertScape.com on 15/07/2023), and by checking guideline organization databases (e.g., the “Canadian Medical Association Infobase of clinical practice guidelines” and the “Istituto Superiore Sanità – Sistema Nazionale Linee Guida”). Two reviewers performed independently the study selection and data extraction phases. We calculated Fleiss’ kappa to evaluate the consistency among guidelines recommendations. 4 Additionally, to summarize the recommendations to triage serious pathologies and the study designs to support recommendations, we computed descriptive statistics (absolute and relative frequencies) and reported the results narratively.

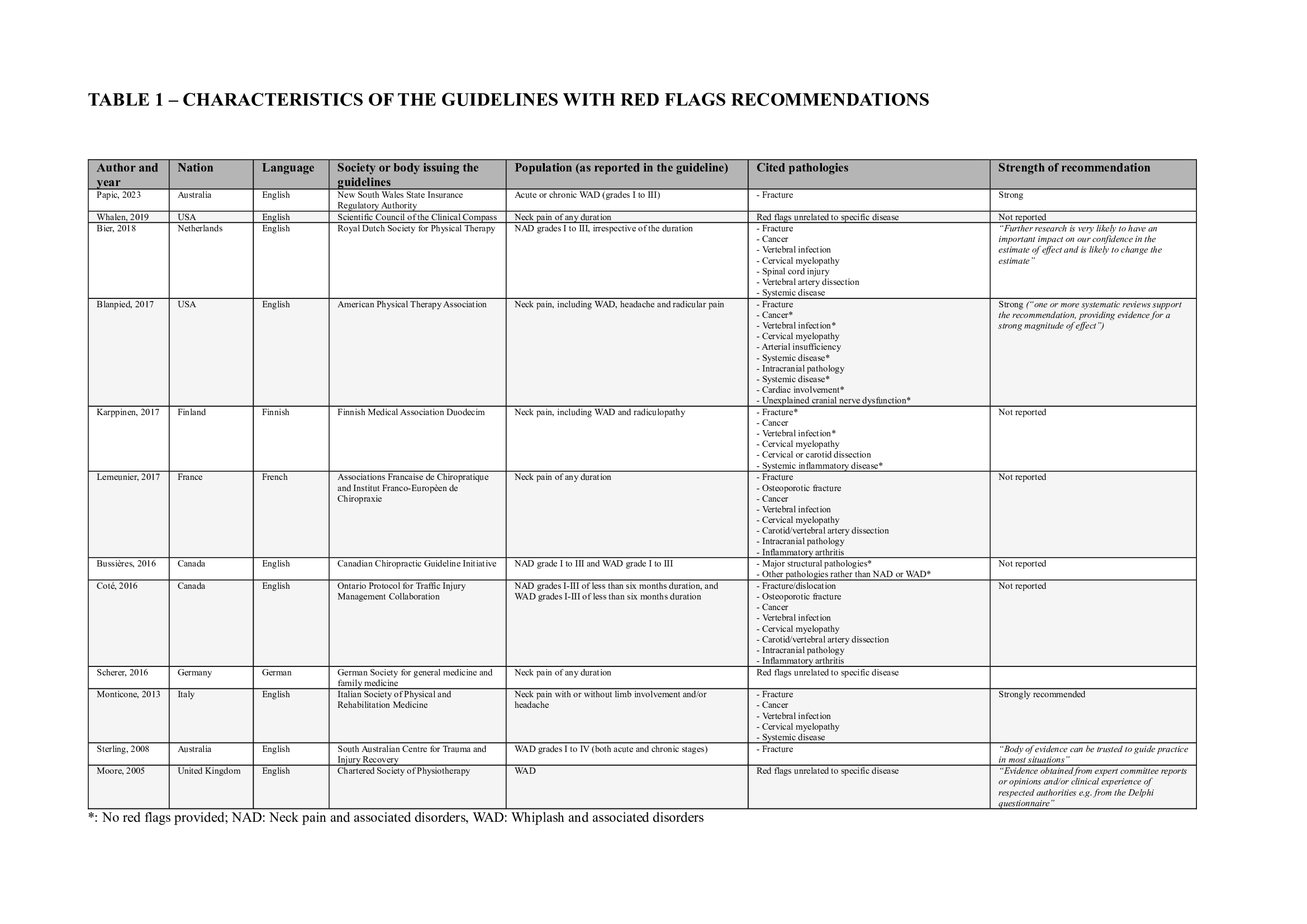

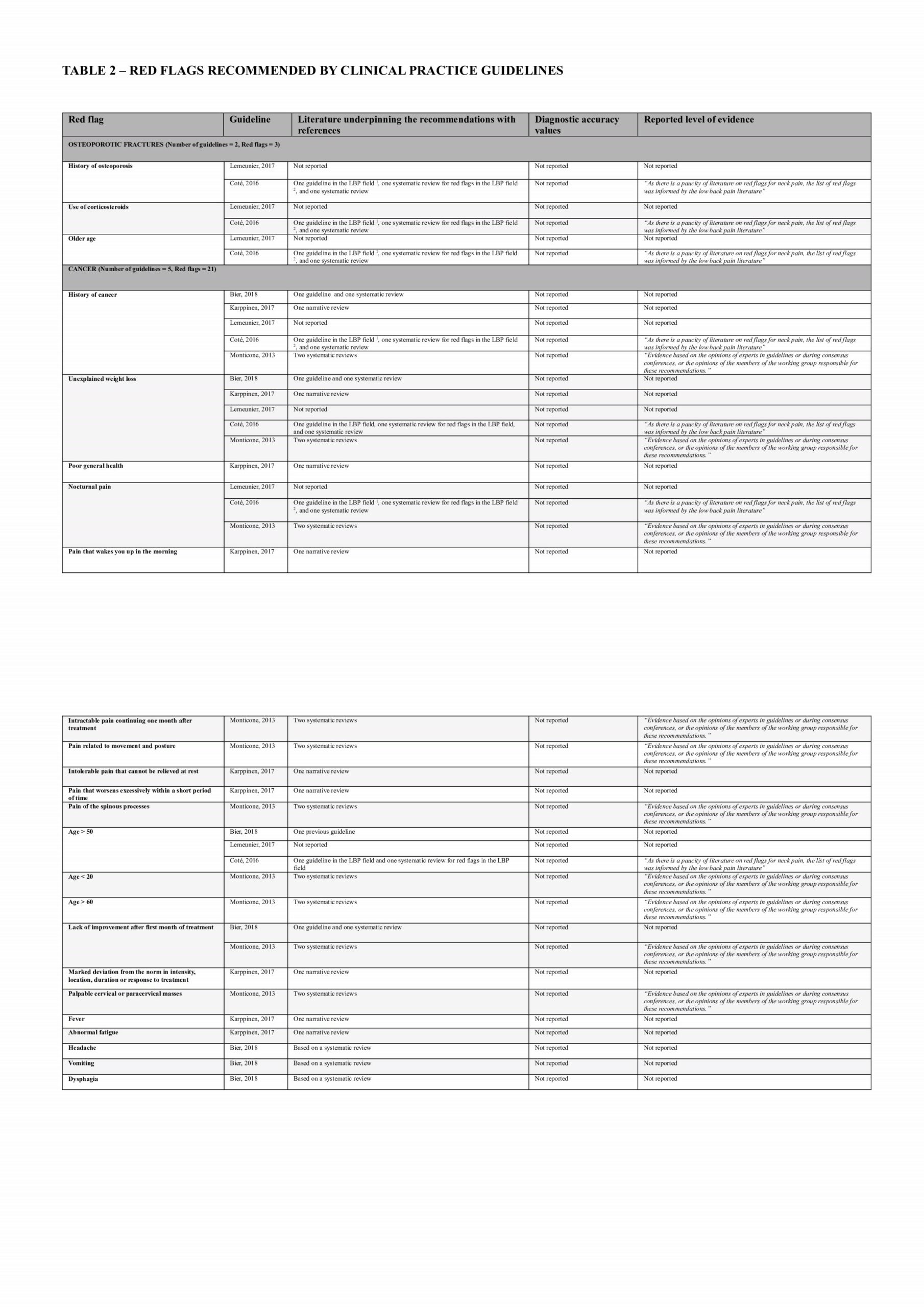

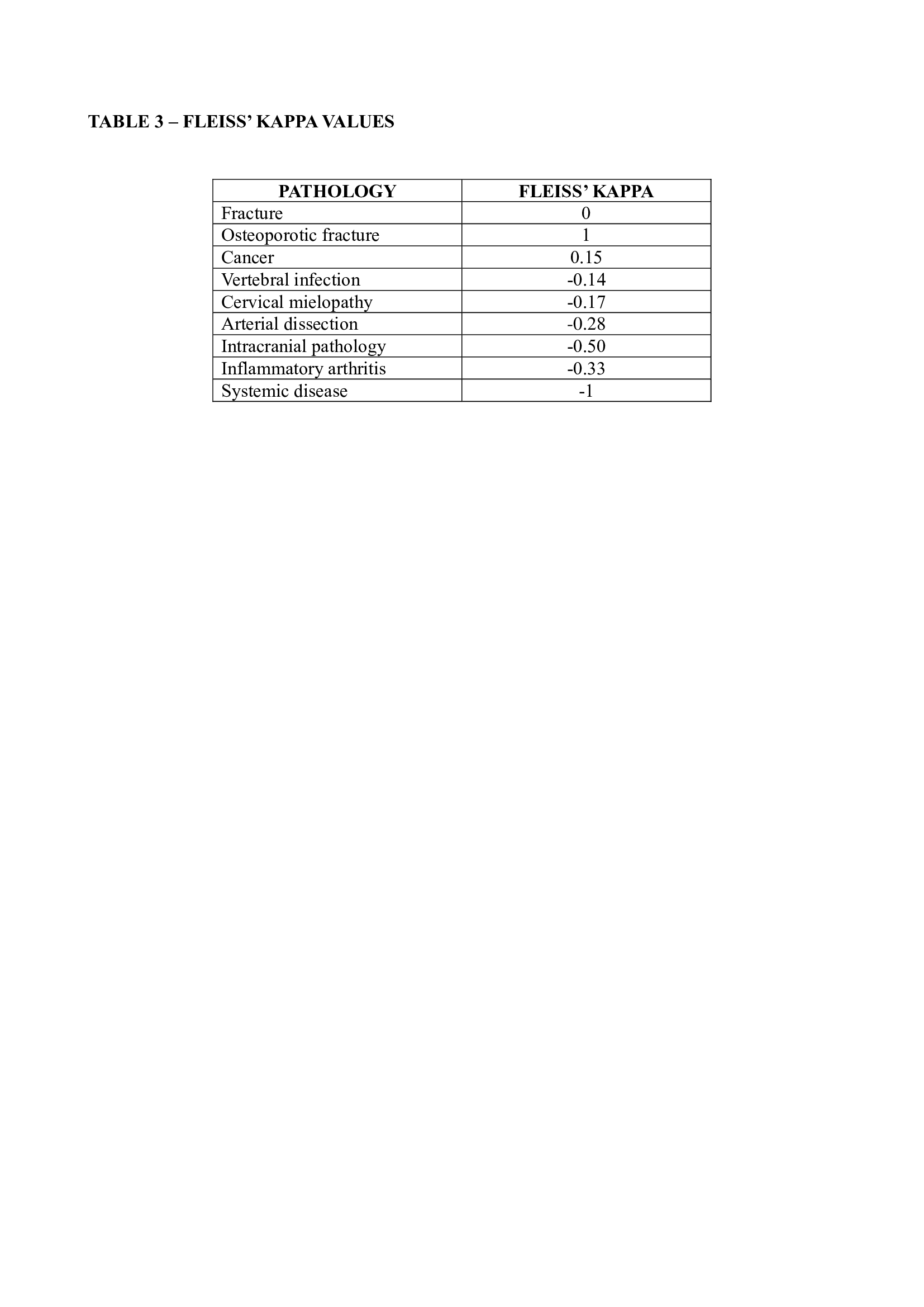

We included 29 guidelines, 12 of which provided information on red flags to screen for serious pathologies (3 for whiplash-associated disorders, 5 for neck pain and associated disorders grade I to III, and 4 for mixed populations) (Table 1). We identified a total of 114 red flags in the guidelines related to fracture, cancer, vertebral infection, myelopathy, spinal cord injury, artery dissection, intracranial pathology, inflammatory arthritis, other systemic diseases, and conditions not related to a specific condition. Overall, there is limited consensus among guidelines regarding red flags for serious pathologies, except for cancer (slight agreement with a Fleiss Kappa of 0.15) and osteoporotic fractures (perfect agreement with a Fleiss’ Kappa of 1) (Table 2 and Table 3). Among all the red flags, only the Canadian C-spine rules for fractures were based on systematic reviews and supported by diagnostic test accuracy values (sensitivity ranging from 90% to 100%; specificity ranging from 42.5% to 45.1%). 10 The remaining red flags were mainly supported by case reports and case series that did not provide direct information on their diagnostic accuracy.

We found that only a few red flags were consistently reported by all the included guidelines (Table 3). Among all the red flags, only the Canadian C-spine rule could be reliably used in clinical practice. All the other red flags have limitations in terms of applicability and diagnostic predictivity, indicating a gap in the literature that should be addressed in future research. This includes conducting secondary studies to systematically summarize the available red flags and primary studies to determine the diagnostic accuracy of signs and symptoms that may suggest a serious medical condition. According to the current limitations of the evidence, clinicians should use the red flags mentioned in the guidelines cautiously and integrate them into a sound clinical reasoning process. Accordingly, when combined within a broad clinical-reasoning framework to determine the level of suspicion about serious pathology, red flags may help clinicians make the best judgment on the appropriate clinical action in a continuous monitoring process. 2