A population-based survey of beliefs about neck pain and its associated disorders: a cross-sectional study.

A population-based survey of beliefs about neck pain and its associated disorders: a cross-sectional study.

Autori

Mirella Forte (Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy).

Stefano Schiavone (Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy).

Federica Nasti (Orthopedic Department, Santa Maria delle Grazie Hospital, Pozzuoli, Naples, Italy)

Fabio Cataldi (Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy)

Daniel Feller (Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. – Provincial Agency for Health of the Autonomous Province of Trento, Trento, Italy. – Centre of Higher Education for Health Sciences of Trento, Trento, Italy.

Firas Mourad (LUNEX, 50, Avenue du Parc des Sports, 4671 Differdange, Luxembourg. – Luxembourg Health & Sport Sciences Research Institute A.s.b.l., 50, Avenue du Parc des Sports, 4671 Differdange, Luxembourg).

Introduction

The combined socio-economic burden from neck pain and whiplash is disproportionately high, with relevant costs due to healthcare use and lost work (Safiri et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2024). Nontraumatic and traumatic neck pain are the fourth leading cause of years lived with disability globally (Shin et al., 2022). It is alarming that this rank has not changed since the 1990s but rather a significant rise of incidence and prevalence is forecasts (Wu et al., 2024). This suggests that prevention and management research over the past 30 years has had minimal impact on its global burden. Negative prognostic factors between these two conditions considerably overlap (Blanpied et al., 2017; Carroll et al., 2008a; Sterling et al., 2011). High initial pain and disability, longer duration of symptoms, reduced range of motion, and psychosocial factors have been reported the more prevalent predictors of poor outcomes (Beales et al., 2016; Carroll et al., 2008a; Shearer et al., 2016; Sterling et al., 2011). Psychological prognostic factors are broadly classified into three dimensions: cognitive (e.g., attitude, belief, perception), emotional (e.g., distress), and behavioral (e.g., coping) (Kazeminasab et al., 2022). Social factors are particularly relevant for workers: their influence is divided under the perception of work and workplace factors (Kazeminasab et al., 2022). These contribute to altering central pain processing and commonly manifest as remote hyperalgesia (Blanpied et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2020) and altered behaviors (Hill and Fritz, 2011; Lang et al., 2012; Nicholas et al., 2011; Vargas-Prada and Coggon, 2015; Vlaeyen and Linton, 2012). However, the mechanisms behind the persistence of symptoms are not yet fully understood and findings are not yet translated into better outcomes (Elliott and Walton, 2017).

Understanding recovery pathways is challenging but insight about the transition to ongoing persistent symptoms will contribute to develop appropriate interventions for those at risk of poor outcomes. Patient-centered care is the practice of caring and respecting the individual patient’s own terms to promote positive outcomes (Cook et al., 2021). However, little attention has been spent around patient perspectives. The whiplash beliefs questionnaire (WBQ) is a questionnaire designed to evaluate subjects’ expectations of recovery and beliefs about neck pain and whiplash injury which has been demonstrated to possess adequate reliability (Symonds et al., 1996). Bostick et al. (Bostick et al., 2009) administered the WBQ to survey laypersons (healthy subjects) in Canada, finding more pessimism about recovery than from work-related neck pain. Ng et al. (Ng et al., 2013) found mostly positive expectations regarding recovery with small cultural differences between laypersons from Australia and Singapore. Although findings from survey research can be difficult to interpret, they have the potential to provide relevant insight not from researchers’ perspective but from the patients one.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has investigated and compared the beliefs of healthy people, or those with a history of neck pain and whiplash. Therefore, the objective of our study is to investigate the beliefs of the general Italian population about neck pain and whiplash.

Methods

An online survey was developed using the online platform Survey Monkey (SVMK Inc., San Mateo, USA) addressed to the Italian general population. Our study is reported in line with the “Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet Surveys” (CHERRIES) and the “Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology” (STROBE) guidelines (von Elm et al., 2007). This study was approved by the Technical-Scientific Committee of the Università degli studi del Molise on the 11/10/2023, with approval protocol n. 23/2023. The authors followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for this study (General Assembly of the World Medical Association, 2014).

QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT

The WBQ was translated and adapted from the most recent version used in a cross-cultural comparison between Australian and Singaporeans layperson’s expectations of recovery (Ng et al., 2013) (appendix 1a and 1b). Two Italian specialized musculoskeletal physiotherapists revised the questionnaire to strengthen the transcultural Italian adaptation and conceptual ambiguity. Then, the questionnaire was piloted by a sample from the general population for additional feedback on wording, response logic and fulfillment duration. Using the original questionnaire and the feedback provided by the pilot stage, respectively strengthened the content and the face validity. To increase the social desirability and reduce the fulfilment duration (i.e., strengthen the response rate), the survey was designed with 27 closed-ended questions (Faletra et al., 2022; Maselli et al., 2021a; Mourad et al., 2021a).

The survey is structured in two sections. The first section investigate sociodemographic information, education level, employment duties, and risk factors, such as having previously suffered from neck pain (i.e., never, in the last 3 months, or for more than 3 months), having a history of whiplash, and having related arm pain using close-ended questions; the second section was designed using the 14-item WBQ to investigate the beliefs on neck pain/whiplash (Ng et al., 2013). In line with the study of Ng et al. (Ng et al., 2013), we also assessed the expectation of recovery with two additional questions and the experienced anxiety and stress with two other additional questions adapted from the Survey of Pain Attitudes (SOPA-35) (Turner et al., 2000). Participants were asked to state their agreement on each item using a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree; 3=not sure; 5=completely agree). All questions were presented in the same order; responses to all questions were mandatory to consider the survey completed. The questionnaire could be completed on any electronic device with Internet access and its completion took approximately 5 minutes.

SETTING AND RECRUIMENT

A web link to the survey was distributed via social media (Facebook and Instagram) from October 2nd, 2023, to February 5th, 2024. To increase the response rate, several invitations were posted, and the survey was shared once a week. A priori sample size was calculated using Dillman’s electronic survey formula (Needham and Vaske, 2008). At the time of the survey, the Italian population was 58.990.000 (Istat, 2023); therefore, the required sample size for this study was 385. As Survey Monkey was used without collecting respondents’ IP addresses, recruitment was anonymous and voluntary; furthermore, the same IP was not allowed to access the survey more than once. No compensation or refunds were offered.

DATA PROCESSING AND ANALYSIS

The final dataset was collected on an encrypted computer, which researchers could access only for the analysis. No sensitive information was collected. The dataset was exported to Microsoft Excel 2020 for the descriptive analysis (frequencies, mean, and standard deviation (SD)).

OUTCOME

For the dependent variables we considered the total WBQ score and four factors that arise from the combinations of questions.

The total WBQ score was calculated from the sum of each question from 1 to 14. To maintain consistency, the scores of items 5 and 13 were reversed as they had been formulated. The maximum score that could be obtained was 70. Higher scores are interpreted as more negative or pessimistic beliefs about the condition.

A previously factorial analysis of the modified version of the WBQ found 4 factors (Bostick et al., 2009). These factors exist within 10 common items in each questionnaire. The items considered for the creation of factors were questions 1 to 14. The four factors are labeled as “recovery pessimism” (sum of questions 2, 6, 10), “beliefs about active coping” (questions 5, 12, 13), “beliefs about passive coping” (questions 11, 14), and “treatment pessimism” (questions 1, 4).

Questions that investigated the expectation of recovery were 15 and 16. Questions that investigated the experienced anxiety and stress were 17 and 18.

PREDICTORS

We identified some predictors of the outcome that, in relation to the WBQ score, could explain the results. These predictors were a history of neck pain, a history of whiplash, and symptoms associated with the conditions. Also, the stage of the condition was considered (i.e., recent or persistent). With associated symptoms we referred to symptoms in the shoulders, arms and hands such as pain, tingling, numbness, loss of strength. Gender, age, marital status, employment, and main type of job were considered confounding factors.

STATISTICAL METHODS

Descriptive statistics are presented as frequency and percentages for categorical variables and mean with the standard deviation for continuous variables.

We investigated the association of neck pain, whiplash, and associated symptoms, with the following dependent variables: total score at the WBQ; the factors “recovery pessimism”, “beliefs about active coping”, “beliefs about passive coping”, “treatment pessimism”; expectation of recovery (questions 15 and 16); anxiety (question 17) and stress (question 18).

We investigated the multivariable association of the independent variables (neck pain, whiplash, and associated symptoms) with all the dependent variables reported above, adjusting by the cofounding variables (i.e., gender, age, marital status, employment, and main type of job). We used a linear regression for the total score of the WBQ and its factors, while for the questions from 15 to 18, we used a proportional odds logistic regression. All the statistical analyses were performed using R (R Core Team, 2021).

Results

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

RESPONDENT CHARACTERISTICS

A total of 1034 participants gave their consent and completed the survey. Among the responders the majority were women (65%, n=673) between 35-50 years of age (37.6%, n=389). Most respondents reported working more than 6 hours per day at the terminal (39.7%, n=411). The majority reported a history of neck pain (60.2%, n=791), and 34.9% (n=361) had whiplash. Only 9.4% (n=98) did not report having suffered from any of the conditions (namely, laypersons). For further sociodemographic baseline details, refer to Table 1.

WORK (items 2 and 10)

42.8% (n=339) of neck pain and 45.3% (n=163) of whiplash sufferers reported to disagree (disagree or strongly disagree) with the sentence “neck pain/whiplash injury will eventually stop you from working”; similarly, 44.9% (n=44) of the laypersons reported to disagree. When asked if “neck pain/whiplash injury means long periods of time off work”, 38.1% (n=301) of neck pain sufferer reported to disagree, while the 38.1% (n=137) of whiplash responders reported to agree (agree and strongly agree); more than one third of laypersons (36.7%, n=36) reported not to be sure and (36.6%, n=36) to agree (appendices 2-5).

TRUST IN HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS (items 4)

42% (n=262) of neck pain and 45.7% (n=165) of whiplash responders reported to strongly disagree with the sentence “doctors/physiotherapists cannot do anything for neck pain/whiplash injury”; accordingly, almost half of laypersons (49.0%, n=48) reported to strongly disagree (appendices 2-5).

MEDICATIONS AND TREATMENTS (items 7, 9, 11, and 14)

When asked if “alternative treatments are the answer to neck pain/whiplash injury”, 34.1% (n=213) of neck pain responders reported not to be sure; 35.7% (n=129) of whiplash responders reported to agree or not to be sure (32.6%, n=118 not sure); most laypersons (37.8%, n=37) reported not to be sure. When asked if “medication is the only way of relieving neck pain/whiplash injury”, responders reported disagreement (neck pain, 70.9%, n=561; whiplash, 68.9%, n=248; laypersons, 61.2%, n=60). Accordingly, most neck pain and whiplash responders disagree (54.6%, n=432; 52.8%, n=190) to the question “simple painkillers are usually enough to control most neck pain/whiplash injury”; laypersons were mostly not sure (40.8%, n=40) (appendices 2-5).

MANAGEMENT AND QUALITY OF LIFE (items 1, 5, 6, and 13)

Most of the responders disagreed with the question “there is no real treatment for neck pain/whiplash injury”(neck pain, 68.2%, n=539; whiplash, 67.5%, n=244; laypersons, 64.2%, n=63). Instead, most of the responders reported to agree when asked “a bad neck/whiplash injury should be exercised” (neck pain, 64.9%, n=513; whiplash, 63%, n=227; laypersons, 65.3%, n=64). Similarly, responders reported to agree with the question “neck pain/whiplash injury makes everything in life worse” (neck pain, 65.1%, n=515; whiplash, 64.7%, n=233; laypersons, 53.1%, n=52). When asked “if you have neck pain/whiplash injury you should try to stay active”, most neck pain patients reported to agree (38.9%, n=307); however, a high number also reported not to be sure (34.5%, n=273). Most whiplash patients reported to agree (40.3%, n=145.4), but a high number also reported not to be sure (30,7%, n=111). Most laypersons (40.8%, n=40) reported not to be sure (appendices 2-5).

RECOVERY EXPECTATION (items 15 and 16)

Whiplash patients reported to disagree (45.9%, n=363) to the question “most neck pain/whiplash injury settles quickly (a few days to a few weeks)”. Most laypersons (48.0%, n=47) reported not to be sure. Most neck pain (43.7%, n=345) and whiplash (46.2%, n=166) patients agreed to the question “you get on with normal activities such as going to work soon after neck pain/whiplash injury”. Laypersons mainly reported to not be sure (35.7%, n=35) (appendix 6-9).

ANXIETY AND STRESS (items 17 and 18)

Most of the responders agreed with the question “anxiety increases the pain you feel”

(neck pain, 75%, n=539; whiplash, 59.2%, n=213; laypersons, 70.4%, n=69) and to the question “stress in your life increases the pain you feel” (neck pain, 83.7%, n=662; whiplash, 81.1%, n=293; laypersons, 73.5%, n=72) (appendix 6-9).

INFERENTIAL STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

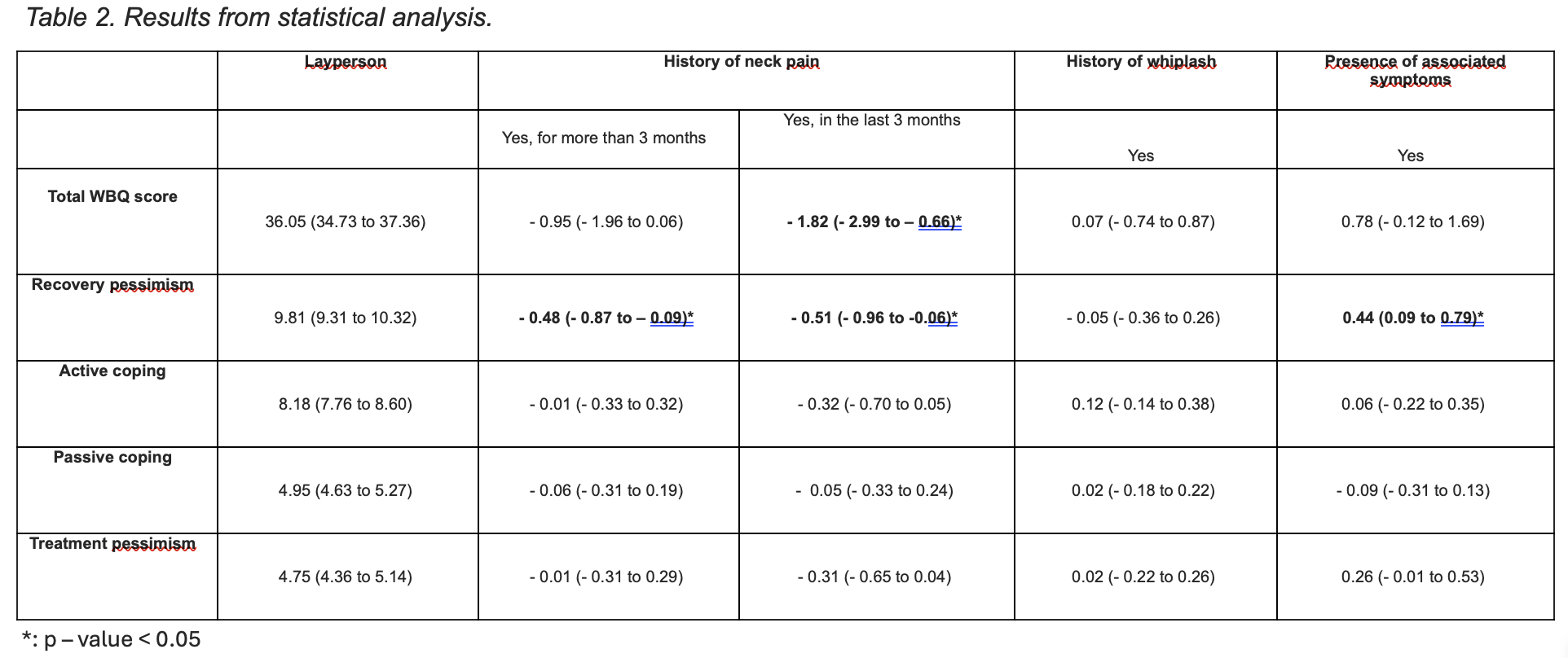

Inferential statistical analysis is summarized in table 2 and 3.

TOTAL WBQ SCORE

A statistically significant difference was only found between laypersons and those with recent neck pain with a mean difference of -1.82 points on the WBQ total score (p<0.01; 95%CI -2.99 to -0.66) (Table 2).

RECOVERY PESSIMISM (items 2, 6, and 10)

A statistically significant difference was found for participants reporting associated symptoms compared to participants who did not report associated symptoms (mean difference=0.44; p=0.01; 95%CI 0.09 to 0.79) (Table 2). Also, we found a statistically significant difference between laypersons and those with recent neck pain (mean difference=-0.51; p<0.01; 95%CI –0.96 to -0.06), and between laypersons and those with neck pain for more than 3 months (mean difference=-0.48; p<0.01; 95%CI –0.87 to -0.09) (Table 2).

ACTIVE COPING, PASSIVE COPING, AND TREATMENT PESSIMISM

No statistically significant differences were found between participants with neck pain, whiplash, or associated symptoms, compared to laypersons (Table 2).

RECOVERY EXPECTATION (items 15 and 16)

A statistically significant difference was found for subjects reporting associated symptoms for the question “most neck pain/whiplash injury settles quickly (a few days to a few weeks)” (odds ratio (OR) 1.38; 95%CI 1.09 to 1.76; p<0.05); however, no difference was found after adjustment for possible confounding factors (OR 1.22; 95%CI 0.94 to 1.59; p>0.05). Furthermore, a statistically significant difference at the unadjusted analysis was also found for participants reporting a history of persistent neck pain (OR 1.37; 95%CI 1.05 to 1.79; p<0.05). However, even in this case, the association was no longer statistically significant in the adjusted analysis (Table 3).

ANXIETY AND STRESS (items 17 and 18)

At the univariable analysis, a statistically significant difference was found for participants reporting recent (OR 1.45; 95%CI 1.01 to 2.09; p<0.05) and persistent neck pain (OR 1.62; 95%CI 1.20 to 2.19; p<0.05) for the question “stress in your life increases the pain you feel”. After adjustment for possible confounding factors, only participants reporting persistent neck pain showed a statistical difference in this item (OR 1.49; 95%CI 1.08 to 2.06; p<0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion and Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing beliefs and perceptions about neck pain and whiplash between patient and layperson. Similarly to Singaporeans, participants of our study were more pessimistic about the items ‘taking time off work’ and ‘eventually stopping one from working’. A lower proportion of the Italian responders agreed that surgery and medication are effective in relieving neck pain and whiplash injury compared to Australians and Singaporeans, but a higher proportion agreed that alternative treatment is effective compared to the Australian sample. Like the Australians and Singaporeans, most Italian responders were positive about exercise and staying active. Similarly to the Canadian sample, more than 60% of the Italian responders agreed with the statement ‘whiplash injury makes everything in life worse’. Like Australians and Singaporeans, less than 25% of the Italian responders disagree that they will return to normal activities soon; while only 23% of Italians agreed to recover quickly like Canadians. Beliefs about anxiety and stress were similar, with more than 70% of participants agreeing that anxiety and stress increased the experience of pain. Although this does not reflect the differences in the prevalence of neck pain and whiplash injury, these differences could be a reflection of cultural nuances between countries. Differences between healthcare and compensation systems could also have had an influence. Italy provides universal public health care and some form of social security benefits to people with injuries that may have impacted the beliefs and expectations of responders compared to other counties.

Overall, few significant findings with large confidence intervals were found. There was a statistically significant lower total score of the WBQ for respondents with recent neck pain compared to laypersons. Although the minimal detectable change for WBQ score is still unknown, the Back Belief Questionnaire (BBQ), from which the WBQ was developed, has a minimal detectable change that ranges from 5.9 to 10.5 points. The mean difference after adjustment of -1.82 points we found does not seem to be an important clinical difference. Moreover, although some studies assess beliefs in other back pain conditions in different countries, only few studies compared beliefs between patients and laypersons. Bostick et al. found no difference in in BBQ scores between those with and without a history of back pain. Our results are also in line with Urquhart et al. who found no relationship between beliefs and pain intensity when comparing no and low pain intensity groups. Many factors contribute to persistent musculoskeletal pain, including biological, psychological, social, and epigenetic factors. However, no firm boundaries among these factors are present. Although psychological factors are commonly investigated separately, all interact with each other. Self-efficacy, psychological distress, and fear were identified as intermediate factors related to the experience of neck pain and developing disability. Particularly, self-efficacy was observed to be consistently associated with disability, affective distress and pain severity. Active coping has been observed to be associated with self-efficacy, while low self-efficacy with passive coping. However, we did not find any differences among conditions nor stage from responders’ perspectives.

Negative recovery expectations, depression or anxiety symptoms, coping, and multiple sites of pain or associated symptoms were found associated with pain intensity/persistence and to predict poor general outcome. Positive recovery expectations were reported to be strongly associated with better work participation in people with low back pain. Interestingly, we found no association for recovery expectation in neck pain/whiplash patients but recovery pessimism was higher for responders with associated symptoms, and in responders with neck pain compared to laypersons. Although no causal inference can’t be done because of the cross-sectional design of our study, this may be due to what items 2, 6 and 10 mean. These items reflect a more pessimist view and the presence of more symptoms could have led to poor recovery. The relationship between mental health symptoms (i.e., anxiety and stress) and diseases is well-established. Stress is mediated by the meaning that person attribute to a disease, the impact of the daily living, and the personal and social resources that the person perceives. We found stress statistically significant higher for responders with persistent neck pain with an OR after adjustment of 1.48 points (95% CI 1.07 to 2.05). Together with stress, anxiety were found to be positively associated with neck pain (with and without associated symptoms) and poorer outcomes. Although not statistically significant, most of the responders of our study agreed that anxiety influences the perception of pain. In our study we only collected the personal perception/beliefs about anxiety, but it should be considered that when anxiety reaches a clinical level it often causes significant social and health impairments.

The biopsychosocial model contributed to raise the issue of the complexity of the concept of health, highlighting the central role of the patient. Therefore, providing emphasis to the person means also to consider the subjective perspective. Prognostic factors and their mutual manifestation are not yet fully understood. Our results challenge and open new perspectives on the influence of psychological (e.g., stress, anxiety, coping and self-efficacy) and social (e.g., healthcare systems and culture) factors on the person thoughts/perception commonly observed in subjects with pain on the cervical spine. The non-linear interaction of these factors with the pain experience of the single person may have been influenced by multiple mediators in a non-controlled setting, leading to the heterogeneous expression of our results.

The high response rate is a strength of our study and confirms the willingness of the population to participate in this study. Unlike previous studies, we also run a multivariable statistical analysis to adjust for potential confounders. One limitation was that the older population could not be easily reached as they use social networks to a lesser extent. Thus, our method of recruitment could have led to selection bias. Another limitation may be the absence of a transcultural validation of the WBQ. A further limitation of the study is the cross-sectional nature of the design: this does not allow to determine causal relationships between observed beliefs and outcomes. Furthermore, in our survey what constitutes a clinically meaningful difference in beliefs is unknown.

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

1. Nordin M, Carragee EJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Weiner SS, Hurwitz EL, Peloso PM, et al. Assessment of Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. febbraio 2008;33(Supplement):S101–22.

2. Hoy D, March L, Woolf A, Blyth F, Brooks P, Smith E, et al. The global burden of neck pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. luglio 2014;73(7):1309–15.

3. Shin DW, Shin JI, Koyanagi A, Jacob L, Smith L, Lee H, et al. Global, regional, and national neck pain burden in the general population, 1990–2019: An analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Neurol. 1 settembre 2022;13:955367.

4. Hoy DG, Protani M, De R, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of neck pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. dicembre 2010;24(6):783–92.

5. Beales D, Fried K, Nicholas M, Blyth F, Finniss D, Moseley GL. Management of musculoskeletal pain in a compensable environment: Implementation of helpful and unhelpful Models of Care in supporting recovery and return to work. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. giugno 2016;30(3):445–67.

6. Areerak K, van der Beek AJ, Janwantanakul P. Recovery from nonspecific neck pain in office workers. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 13 settembre 2018;31(4):727–34.

7. Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, Devaney LL, Clewley D, Walton DM, et al. Neck Pain: Revision 2017: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. luglio 2017;47(7):A1–83.

8. Bier JD, Scholten-Peeters WGM, Staal JB, Pool J, van Tulder MW, Beekman E, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Physical Therapy Assessment and Treatment in Patients With Nonspecific Neck Pain. Phys Ther. 1 marzo 2018;98(3):162–71.

9. Walton DM, Elliott JM. An Integrated Model of Chronic Whiplash-Associated Disorder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. luglio 2017;47(7):462–71.

10. Guez M. Chronic neck pain. An epidemiological, psychological and SPECT study with emphasis on whiplash-associated disorders. Acta Orthop Suppl. febbraio 2006;77(320):preceding 1, 3-33.

11. Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Cassidy JD, Haldeman S, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 15 febbraio 2008;33(4 Suppl):S83-92.

12. Sleijser-Koehorst MLS, Coppieters MW, Heymans MW, Rooker S, Verhagen AP, Scholten-Peeters GGM. Clinical course and prognostic models for the conservative management of cervical radiculopathy: a prospective cohort study. Eur Spine J. novembre 2018;27(11):2710–9.

13. Casey PP, Feyer AM, Cameron ID. Course of recovery for whiplash associated disorders in a compensation setting. Injury. novembre 2015;46(11):2118–29.

14. Kamper SJ, Rebbeck TJ, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Sterling M. Course and prognostic factors of whiplash: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 15 settembre 2008;138(3):617–29.

15. Sterling M, Hendrikz J, Kenardy J. Compensation claim lodgement and health outcome developmental trajectories following whiplash injury: A prospective study. Pain. luglio 2010;150(1):22–8.

16. Côté P, Wong JJ, Sutton D, Shearer HM, Mior S, Randhawa K, et al. Management of neck pain and associated disorders: A clinical practice guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur Spine J. 1 luglio 2016;25(7):2000–22.

17. Bussières AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Hayden J, et al. The Treatment of Neck Pain–Associated Disorders and Whiplash-Associated Disorders: A Clinical Practice Guideline. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. ottobre 2016;39(8):523-564.e27.

18. Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Hoy D, Buchbinder R, Mansournia MA, Bettampadi D, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neck pain in the general population, 1990-2017: systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ. 26 marzo 2020;368:m791.

19. Xie Y, Jun D, Thomas L, Coombes BK, Johnston V. Comparing Central Pain Processing in Individuals With Non-Traumatic Neck Pain and Healthy Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2020;21(11–12):1101–24.

20. Parikh P, Santaguida P, Macdermid J, Gross A, Eshtiaghi A. Comparison of CPG’s for the diagnosis, prognosis and management of non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. dicembre 2019;20(1):81.

21. Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: 12 years on. Pain. giugno 2012;153(6):1144–7.

22. Lang J, Ochsmann E, Kraus T, Lang JWB. Psychosocial work stressors as antecedents of musculoskeletal problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis of stability-adjusted longitudinal studies. Soc Sci Med 1982. ottobre 2012;75(7):1163–74.

23. Hill JC, Fritz JM. Psychosocial influences on low back pain, disability, and response to treatment. Phys Ther. maggio 2011;91(5):712–21.

24. Vargas-Prada S, Coggon D. Psychological and psychosocial determinants of musculoskeletal pain and associated disability. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. giugno 2015;29(3):374–90.

25. Elliott JM, Walton DM. How Do We Meet the Challenge of Whiplash? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. luglio 2017;47(7):444–6.

26. Sterling M, Carroll LJ, Kasch H, Kamper SJ, Stemper B. Prognosis after whiplash injury: where to from here? Discussion paper 4. Spine. 1 dicembre 2011;36(25 Suppl):S330-334.

27. Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Amiri P, Pourfathi H, Araj-Khodaei M, Sullman MJM, et al. Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 3 gennaio 2022;23(1):26.

28. Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J, Darnell R. Physical and psychological factors predict outcome following whiplash injury. Pain. marzo 2005;114(1):141–8.

29. Cook CE, Denninger T, Lewis J, Diener I, Thigpen C. Providing value-based care as a physiotherapist. Arch Physiother. 20 aprile 2021;11(1):12.

30. Bostick GP, Ferrari R, Carroll LJ, Russell AS, Buchbinder R, Krawciw D, et al. A population-based survey of beliefs about neck pain from whiplash injury, work-related neck pain, and work-related upper extremity pain. Eur J Pain Lond Engl. marzo 2009;13(3):300–4.

31. Ng TS, Bostick G, Pedler A, Buchbinder R, Vicenzino B, Sterling M. Laypersons’ expectations of recovery and beliefs about whiplash injury: A cross-cultural comparison between Australians and Singaporeans: Laypersons’ whiplash beliefs. Eur J Pain. settembre 2013;17(8):1234–42.